for _ in range(3):

print(get_joke(f="application/json"))The shovel was a ground-breaking invention.

My wife is on a tropical fruit diet, the house is full of stuff. It is enough to make a mango crazy.

Where do cats write notes?

Scratch Paper!Rich Leyshon

July 14, 2024

“A day without laughter is a day wasted.” Charlie Chaplin

pytest is a testing package for the python framework. It is broadly used to quality assure code logic. This article discusses the dark art of mocking, why you should do it and the nuts and bolts of implementing mocked tests. This blog is the fourth in a series of blogs called pytest in plain English, favouring accessible language and simple examples to explain the more intricate features of the pytest package.

For a wealth of documentation, guides and how-tos, please consult the pytest documentation.

Code often has external dependencies:

As developers cannot control the behaviour of those dependencies, they would not write tests dependent upon them. In order to test their source code that depends on these services, developers need to replace the properties of these services when the test suite runs. Injecting replacement values into the code at runtime is generally referred to as mocking. Mocking these values means that developers can feed dependable results to their code and make reliable assertions about the code’s behaviour, without changes in the ‘outside world’ affecting outcomes in the system under test.

Developers who write unit tests may also mock their own code. The “unit” in the term “unit test” implies complete isolation from external dependencies. Mocking is an indispensible tool in achieving that isolation within a test suite. It ensures that code can be efficiently verified in any order, without dependencies on other elements in your codebase. However, mocking also adds to code complexity, increasing cognitive load and generally making things harder to debug.

This article intends to discuss clearly. It doesn’t aim to be clever or impressive. Its aim is to extend understanding without overwhelming the reader. The code may not always be optimal, favouring a simplistic approach wherever possible.

Programmers with a working knowledge of python, HTTP requests and some familiarity with pytest and packaging. The type of programmer who has wondered about how to follow best practice in testing python code.

This blog is accompanied by code in this repository. The main branch provides a template with the minimum structure and requirements expected to run a pytest suite. The repo branches contain the code used in the examples of the following sections.

Feel free to fork or clone the repo and checkout to the example branches as needed.

The example code that accompanies this article is available in the mocking branch of the repo.

Mocking is one of the trickier elements of testing. It’s a bit niche and is often perceived to be too hacky to be worth the effort. The options for mocking in python are numerous and this adds to the complexity of many example implementations you will find online.

There is also a compromise in simplicity versus flexibility. Some of the options available are quite involved and can be adapted to the nichest of cases, but may not be the best option for those new to mocking. With this in mind, I present 3 alternative methods for mocking python source code. So if you’ll forgive me, this is the first of the pytest in plain English series where I introduce alternative testing practices from beyond the pytest package.

pytest fixture designed for mocking. The origin of the fixture’s name is debated but potentially arose from the term ‘guerrilla patch’ which may have been misinterpreted as ‘gorilla patch’. This is the concept of modifying source code at runtime, which probably sounds a bit like ‘monkeying with the code’.unittest package.mockito is robust and secure.Mocking has a bunch of synonyms & related language which can be a bit off-putting. All of the below terms are associated with mocking. Some may be preferred to the communities of specific programming frameworks over others.

| Term | Brief Meaning | Frameworks/Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Mocking | Creating objects that simulate the behaviour of real objects for testing | Mockito (Java), unittest.mock (Python), Jest (JavaScript), Moq (.NET) |

| Spying | Observing and recording method calls on real objects | Mockito (Java), Sinon (JavaScript), unittest.mock (Python), RSpec (Ruby) |

| Stubbing | Replacing methods with predefined behaviours or return values | Sinon (JavaScript), RSpec (Ruby), PHPUnit (PHP), unittest.mock (Python) |

| Patching | Temporarily modifying or replacing parts of code for testing | unittest.mock (Python), pytest-mock (Python), PowerMock (Java) |

| Faking | Creating simplified implementations of complex dependencies | Faker (multiple languages), Factory Boy (Python), FactoryGirl (Ruby) |

| Dummy Objects | Placeholder objects passed around but never actually used | Can be created in any testing framework |

This section will walk through some code that uses HTTP requests to an external service and how we can go about testing the code’s behaviour without relying on that service being available. Feel free to clone the repository and check out to the example code branch to run the examples.

The purpose of the code is to retrieve jokes from https://icanhazdadjoke.com/ like so:

The shovel was a ground-breaking invention.

My wife is on a tropical fruit diet, the house is full of stuff. It is enough to make a mango crazy.

Where do cats write notes?

Scratch Paper!The jokes are provided by https://icanhazdadjoke.com/ and are not curated by me. In my testing of the service I have found the jokes to be harmless fun, but I cannot guarantee that. If an offensive joke is returned, this is unintentional but let me know about it and I will generate new jokes.

The function get_joke() uses 2 internals:

_query_endpoint() Used to construct the HTTP request with required headers and user agent._handle_response() Used to catch HTTP errors, or to pull the text out of the various response formats."""Retrieve dad jokes available."""

import requests

def _query_endpoint(

endp:str, usr_agent:str, f:str,

) -> requests.models.Response:

"""Utility for formatting query string & requesting endpoint."""

HEADERS = {

"User-Agent": usr_agent,

"Accept": f,

}

resp = requests.get(endp, headers=HEADERS)

return respKeeping separate, the part of the codebase that you wish to target for mocking is often the simplest way to go about things. The target for our mocking will be the command that integrates with the external service, so requests.get() here.

The use of requests.get() in the code above depends on a few things:

We’ll need to consider those dependencies when mocking. Once we return a response from the external service, we need a utility to handle the various statuses of that response:

"""Retrieve dad jokes available."""

import requests

def _query_endpoint(

endp:str, usr_agent:str, f:str,

) -> requests.models.Response:

...

def _handle_response(r: requests.models.Response) -> str:

"""Utility for handling reponse object & returning text content.

Parameters

----------

r : requests.models.Response

Response returned from webAPI endpoint.

Raises

------

NotImplementedError

Requested format `f` was not either 'text/plain' or 'application/json'.

requests.HTTPError

HTTP error was encountered.

"""

if r.ok:

c_type = r.headers["Content-Type"]

if c_type == "application/json":

content = r.json()

content = content["joke"]

elif c_type == "text/plain":

content = r.text

else:

raise NotImplementedError(

"This client accepts 'application/json' or 'text/plain' format"

)

else:

raise requests.HTTPError(

f"{r.status_code}: {r.reason}"

)

return contentOnce _query_endpoint() gets us a response, we can feed it into _handle_response(), where different logic is executed depending on the response’s properties. Specifically, any response we want to mock would need the following:

{"content_type": "plain/text"}json() method.text, status_code and reason attributes.Finally, the above functions get wrapped in the get_joke() function below:

"""Retrieve dad jokes available."""

import requests

def _query_endpoint(

endp:str, usr_agent:str, f:str,

) -> requests.models.Response:

...

def _handle_response(r: requests.models.Response) -> str:

...

def get_joke(

endp:str = "https://icanhazdadjoke.com/",

usr_agent:str = "datasavvycorner.com (https://github.com/r-leyshon/pytest-fiddly-examples)",

f:str = "text/plain",

) -> str:

"""Request a joke from icanhazdadjoke.com.

Ask for a joke in either plain text or JSON format. Return the joke text.

Parameters

----------

endp : str, optional

Endpoint to query, by default "https://icanhazdadjoke.com/"

usr_agent : str, optional

User agent value, by default

"datasavvycorner.com (https://github.com/r-leyshon/pytest-fiddly-examples)"

f : str, optional

Format to request eg "application.json", by default "text/plain"

Returns

-------

str

Joke text.

"""

r = _query_endpoint(endp=endp, usr_agent=usr_agent, f=f)

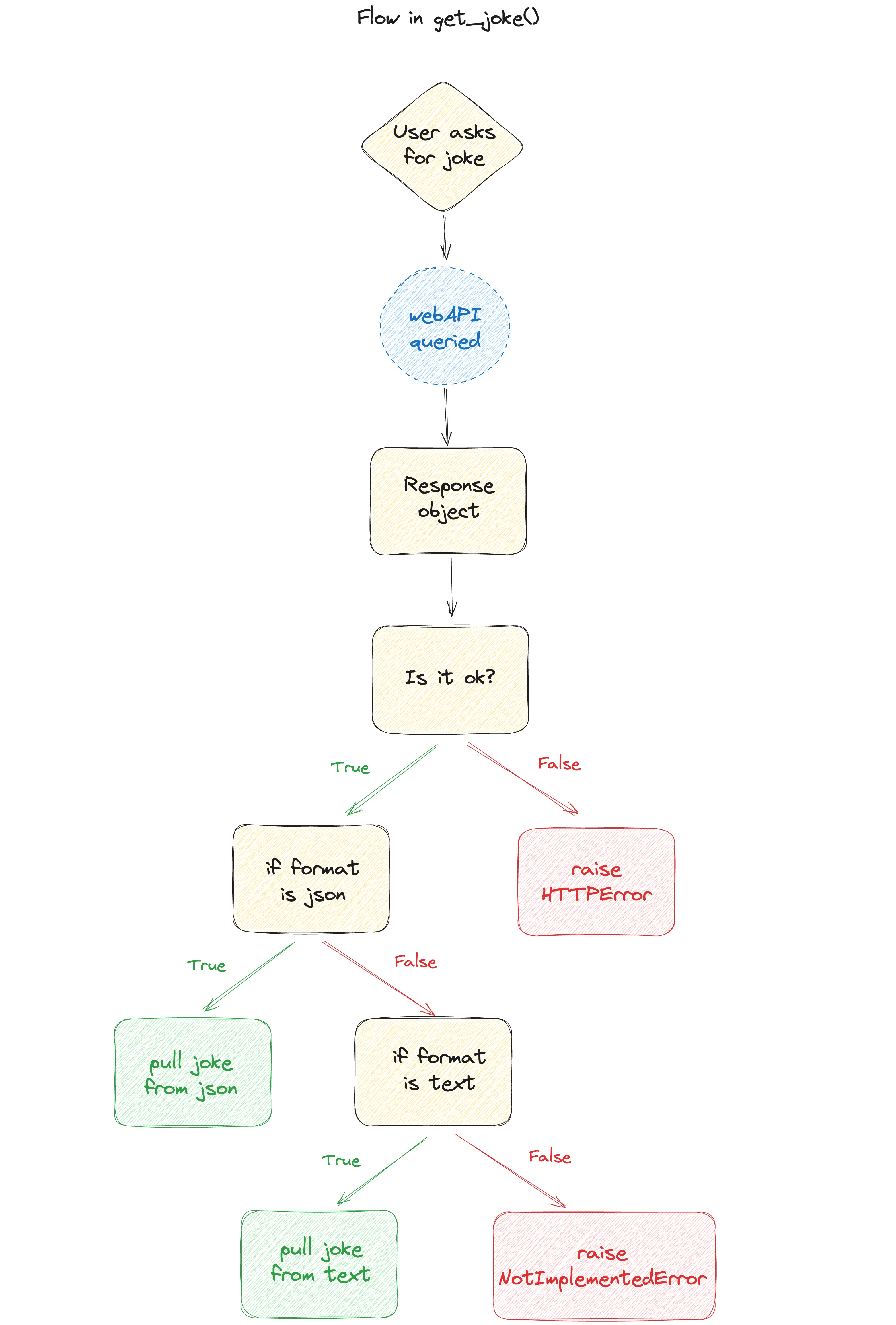

return _handle_response(r)The behaviour in get_joke() is summarised in the flowchart below:

There are 4 outcomes to check, coloured red and green in the process chart above.

get_joke() successfully returns joke text when the user asked for json format.get_joke() successfully returns joke text when the user asked for plain text.get_joke() raises NotImplementedError if any other valid format is asked for. Note that the API also accepts HTML and image formats, though parsing the joke text out of those is more involved and beyond the scope of this blog.get_joke() raises a HTTPError if the response from the API was not ok.Note that the event that we wish to target for mocking is highlighted in blue - we don’t want our tests to execute any real requests.

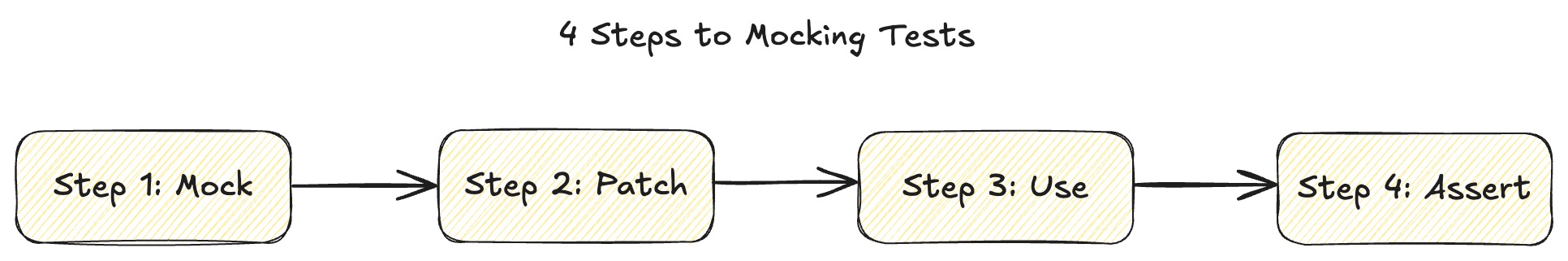

The strategy for testing this function without making requests to the web API is composed of 4 similar steps, regardless of the package used to implement the mocking.

In the examples that follow, I will label the equivalent steps for the various mocking implementations.

What hard-coded text shall I use for my expected joke? I’ll create a fixture that will serve up this joke text to all of the test modules used below. I’m only going to define it once and then refer to it throughout several examples below. So it needs to be a pretty memorable, awesome joke.

Being a Welshman, I may be a bit biased. But that’s a pretty memorable dad joke in my opinion. This joke will be available to every test within my test suite when I execute pytest from the command line. The assertions that we will use when using get_joke() will expect this string to be returned. If some other joke is returned, then we have not mocked correctly and an HTTP request was sent to the API.

I’ll start with an example of how to mock get_joke() completely. This is an intentionally bad idea. In doing this, the test won’t actually be executing any of the code, just returning a hard-coded value for the joke text. All this does is prove that the mocking works as expected and has nothing to do with the logic in our source code.

So why am I doing it? Hopefully I can illustrate the most basic implementation of mocking in this way. I’m not having to think about how I can mock a response object with all the required properties. I just need to provide some hard coded text.

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_monkeypatched_entirely(monkeypatch, ULTI_JOKE):

"""Completely replace the entire get_joke return value.

Not a good idea for testing as none of our source code will be tested. But

this demonstrates how to entirely scrub a function and replace with any

placeholder value at pytest runtime."""

# step 1

def _mock_joke():

"""Return the joke text.

monkeypatch.setattr expects the value argument to be callable. In plain

English, a function or class."""

return ULTI_JOKE

# step 2

monkeypatch.setattr(

target=example_pkg.only_joking,

name="get_joke",

value=_mock_joke

)

# step 3 & 4

# Use the module's namespace to correspond with the monkeypatch

assert example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke() == ULTI_JOKE _mock_joke to serve the text in the required format.monkeypatch.setattr() is able to take the module namespace that we imported as the target. This must be the namespace where the function (or variable etc) is defined.import example_pkg.only_joking as jk). Be sure to update your reference to get_joke() in step 2 and 3 to match your import statement.from unittest.mock import MagicMock, patch

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_magicmocked_entirely(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Completely replace the entire get_joke return value.

Not a good idea for testing as none of our source code will be tested. But

this demonstrates how to entirely scrub a function and replace with any

placeholder value at pytest runtime."""

# step 1

_mock_joke = MagicMock(return_value=ULTI_JOKE)

# step 2

with patch("example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke", _mock_joke):

# step 3

joke = example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke()

# step 4

assert joke == ULTI_JOKEMagicMock() allows us to return static values as mock objects.get_joke(), be sure to call reference the namespace in the same way as to your patch in step 2.from mockito import when, unstub

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_mockitoed_entirely(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Completely replace the entire get_joke return value.

Not a good idea for testing as none of our source code will be tested. But

this demonstrates how to entirely scrub a function and replace with any

placeholder value at pytest runtime."""

# step 1 & 2

when(example_pkg.only_joking).get_joke().thenReturn(ULTI_JOKE)

# step 3

joke = example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke()

# step 4

assert joke == ULTI_JOKE

unstub()mockito’s intuitive when(...).thenReturn(...) pattern allows you to reference any object within the imported namespace. Like with MagicMock, the static string ULTI_JOKE can be referenced.get_joke(), be sure to call reference the namespace in the same way as to your patch in step 2.get_joke(). If you did not unstub(), the patch to get_joke() would persist through the rest of your tests.mockito allows you to implicitly unstub() by using the context manager with.monkeypatch() without OOPSomething I’ve noticed about the pytest documentation for monkeypatch, is that it gets straight into mocking with Object Oriented Programming (OOP). While this may be a bit more convenient, it is certainly not a requirement of using monkeypatch and definitely adds to the cognitive load for new users. This first example will mock the value of requests.get without using classes.

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

def test_get_joke_monkeypatched_no_OOP(monkeypatch, ULTI_JOKE):

# step 1: Mock the response object

def _mock_response(*args, **kwargs):

resp = requests.models.Response()

resp.status_code = 200

resp._content = ULTI_JOKE.encode("UTF8")

resp.headers = {"Content-Type": "text/plain"}

return resp

# step 2: Patch requests.get

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", _mock_response)

# step 3: Use requests.get

joke = get_joke()

# step 4: Assert

assert joke == ULTI_JOKE, f"Expected:\n'{ULTI_JOKE}\nFound:\n{joke}'"

# will also work for json format

joke = get_joke(f="application/json")

assert joke == ULTI_JOKE, f"Expected:\n'{ULTI_JOKE}\nFound:\n{joke}'"requests.get() will be a response object. We need to mock this object with the methods and attributes required by the _handle_response() function._content attribute, the mocked joke will be returned for both JSON and plain text formats - very convenient!In this example, we demonstrate the same functionality as above, but the monkeypatch example will use an object-oriented design pattern. This approach more closely follows that of the pytest documentation. As before, MagicMock and mockito examples will be included.

The purpose of this test is to test the outcome of get_joke() when the user specifies a json format.

import pytest

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

@pytest.fixture

def _mock_response(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Return a class instance that will mock all the properties of a response

object that get_joke needs to work.

"""

HEADERS_MAP = {

"text/plain": {"Content-Type": "text/plain"},

"application/json": {"Content-Type": "application/json"},

"text/html": {"Content-Type": "text/html"},

}

class MockResponse:

def __init__(self, f, *args, **kwargs):

self.ok = True

self.f = f

self.headers = HEADERS_MAP[f] # header corresponds to format that

# the user requested

self.text = ULTI_JOKE

def json(self):

if self.f == "application/json":

return {"joke": ULTI_JOKE}

return None

return MockResponse

def test_get_joke_json_monkeypatched(monkeypatch, _mock_response, ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for JSON joke.

Test get_joke using the mock class fixture. This approach is the

implementation suggested in the pytest docs.

"""

# step 1: Mock

def _mock_get_good_resp(*args, **kwargs):

"""Return fixtures with the correct header.

If the test uses "text/plain" format, we need to return a MockResponse

class instance with headers attribute equal to

{"Content-Type": "text/plain"}, likewise for JSON.

"""

f = kwargs["headers"]["Accept"]

return _mock_response(f)

# Step 2: Patch

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", _mock_get_good_resp)

# Step 3: Use

j_json = get_joke(f="application/json")

# Step 4: Assert

assert j_json == ULTI_JOKE, f"Expected:\n'{ULTI_JOKE}\nFound:\n{j_json}'"_handle_response().pytest fixture.requests.get(). This will allow our class instance to retrieve the appropriate header from the HEADERS_MAP dictionary.As you may appreciate, this does not appear to be the most straight forward implementation, but it will allow us to test when the user asks for JSON, plain text or HTML formats. In the above test, we assert against JSON format only.

from unittest.mock import MagicMock, patch

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

def test_get_joke_json_magicmocked(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for JSON joke."""

# step 1: Mock

mock_response = MagicMock(spec=requests.models.Response)

mock_response.ok = True

mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "application/json"}

mock_response.json.return_value = {"joke": ULTI_JOKE}

# step 2: Patch

with patch("requests.get", return_value=mock_response):

# step 3: Use

joke = get_joke(f="application/json")

# step 4: Assert

assert joke == ULTI_JOKEMagicMock() can return a mock object with a specification designed to mock response objects. Super useful.MagicMock without the need for an intermediate class.monkeypatch approach, this appears to be more straight forward and maintainable.from mockito import when, unstub

import requests

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_json_mockitoed(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for JSON joke."""

# step 1: Mock

_mock_response = requests.models.Response()

_mock_response.status_code = 200

_mock_response._content = b'{"joke": "' + ULTI_JOKE.encode("utf-8") + b'"}'

_mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "application/json"}

# step 2: Patch

when(requests).get(...).thenReturn(_mock_response)

# step 3: Use

joke = example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke(f="application/json")

# step 4: Assert

assert joke == ULTI_JOKE

unstub()json package. json.dumps(dict).encode("UTF8") will format the content dictionary in the required way.mockito’s when() approach will allow you to access the methods of the object that is being patched, in this case requests.mockito allows you to pass the ... argument to a patched method, to indicate that whatever arguments were passed to get(), return the specified mock value.... will allow you to set different return values depending on argument values received by get().The purpose of this test is to check the outcome when the user specifies a plain/text format while using get_joke().

import pytest

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

@pytest.fixture

def _mock_response(ULTI_JOKE):

"""The same fixture as was used for testing JSON format"""

...

def test_get_joke_text_monkeypatched(monkeypatch, _mock_response, ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for plain text joke."""

# step 1: Mock

def _mock_get_good_resp(*args, **kwargs):

f = kwargs["headers"]["Accept"]

return _mock_response(f)

# step 2: Patch

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", _mock_get_good_resp)

# step 3: Use

j_txt = get_joke(f="text/plain")

# step 4: Assert

assert j_txt == ULTI_JOKE, f"Expected:\n'{ULTI_JOKE}\nFound:\n{j_txt}'"HEADERS_MAP dictionary.from unittest.mock import MagicMock, patch

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

def test_get_joke_text_magicmocked(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for plain text joke."""

# step 1: Mock

mock_response = MagicMock(spec=requests.models.Response)

mock_response.ok = True

mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "text/plain"}

mock_response.text = ULTI_JOKE

# step 2: Patch

with patch("requests.get", return_value=mock_response):

# step 3: Use

joke = get_joke(f="text/plain")

# step 4: Assert

assert joke == ULTI_JOKEfrom mockito import when, unstub

import requests

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_text_mockitoed(ULTI_JOKE):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for plain text joke."""

# step 1: Mock

mock_response = requests.models.Response()

mock_response.status_code = 200

mock_response._content = ULTI_JOKE.encode("utf-8")

mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "text/plain"}

# step 2: Patch

when(requests).get(...).thenReturn(mock_response)

# step 3: Use

joke = example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke(f="text/plain")

# step 4: Assert

assert joke == ULTI_JOKE

unstub()This test will check the outcome of what happens when the user asks for a format other than text or JSON format. As the webAPI also offers image or HTML formats, a response 200 (ok) would be returned from the service. But I was too busy (lazy) to extract the text from those formats.

import pytest

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

@pytest.fixture

def _mock_response(ULTI_JOKE):

"""The same fixture as was used for testing JSON format"""

...

def test_get_joke_not_implemented_monkeypatched(

monkeypatch, _mock_response):

"""Test behaviour when user asked for HTML response."""

# step 1: Mock

def _mock_get_good_resp(*args, **kwargs):

f = kwargs["headers"]["Accept"]

return _mock_response(f)

# step 2: Patch

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", _mock_get_good_resp)

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(

NotImplementedError,

match="This client accepts 'application/json' or 'text/plain' format"):

get_joke(f="text/html")HEADERS_MAP dictionary.with pytest.raises) which catches the raised exception and stops it from terminating our pytest session.match argument can take a regular expression, so that wildcard patterns can be used. This allows matching of part of the exception message.import pytest

import requests

from unittest.mock import MagicMock, patch

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

def test__handle_response_not_implemented_magicmocked():

"""Test behaviour when user asked for HTML response."""

# step 1: Mock

mock_response = MagicMock(spec=requests.models.Response)

mock_response.ok = True

mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "text/html"}

# step 2: Patch

with patch("requests.get", return_value=mock_response):

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(

NotImplementedError,

match="client accepts 'application/json' or 'text/plain' format"):

get_joke(f="text/html")from mockito import when, unstub

import requests

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_not_implemented_mockitoed():

"""Test behaviour when user asked for HTML response."""

# step 1: Mock

mock_response = requests.models.Response()

mock_response.status_code = 200

mock_response.headers = {"Content-Type": "text/html"}

# step 2: Patch

when(

example_pkg.only_joking

)._query_endpoint(...).thenReturn(mock_response)

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(

NotImplementedError,

match="This client accepts 'application/json' or 'text/plain' format"):

example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke(f="text/html")

unstub()In this test, we simulate a bad response from the webAPI, which could arise for a number of reasons:

These conditions are those that we have the least control over and therefore have the greatest need for mocking.

import pytest

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke, _handle_response

@pytest.fixture

def _mock_bad_response():

class MockBadResponse:

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.ok = False

self.status_code = 404

self.reason = "Not Found"

return MockBadResponse

def test_get_joke_http_error_monkeypatched(

monkeypatch, _mock_bad_response):

"""Test bad HTTP response."""

# step 1: Mock

def _mock_get_bad_response(*args, **kwargs):

f = kwargs["headers"]["Accept"]

return _mock_bad_response(f)

# step 2: Patch

monkeypatch.setattr(requests, "get", _mock_get_bad_response)

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(requests.HTTPError, match="404: Not Found"):

get_joke()get_joke(), for example different string values passed as the endpoint.get_joke(), you may wish to retry the request for certain HTTP error status codes. The ability to provide mocked objects that reliably serve those statuses allow you to deterministically validate your code’s behaviour.import pytest

from unittest.mock import MagicMock, patch

import requests

from example_pkg.only_joking import get_joke

def test_get_joke_http_error_magicmocked():

"""Test bad HTTP response."""

# step 1: Mock

_mock_response = MagicMock(spec=requests.models.Response)

_mock_response.ok = False

_mock_response.status_code = 404

_mock_response.reason = "Not Found"

# step 2: Patch

with patch("requests.get", return_value=_mock_response):

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(requests.HTTPError, match="404: Not Found"):

get_joke()from mockito import when, unstub

import requests

import example_pkg.only_joking

def test_get_joke_http_error_mockitoed():

"""Test bad HTTP response."""

# step 1: Mock

_mock_response = requests.models.Response()

_mock_response.status_code = 404

_mock_response.reason = "Not Found"

# step 2: Patch

when(example_pkg.only_joking)._query_endpoint(...).thenReturn(

_mock_response)

# step 3 & 4 Use (try to but exception is raised) & Assert

with pytest.raises(requests.HTTPError, match="404: Not Found"):

example_pkg.only_joking.get_joke()

unstub()We have thoroughly tested our code using approaches that mock the behaviour of an external webAPI. We have also seen how to implement those tests with 3 different packages.

I hope that this has provided you with enough introductory material to begin mocking tests if you have not done so before. If you find that your specific use case for mocking is quite nuanced and fiddly (it’s likely to be that way), then the alternative implementations presented here can help you to understand how to solve your specific mocking dilemma.

One final quote for those developers having their patience tested by errors attempting to implement mocking:

“He who laughs last, laughs loudest.”

…or she for that matter: Don’t give up!

If you spot an error with this article, or have a suggested improvement then feel free to raise an issue on GitHub.

Happy testing!

To past and present colleagues who have helped to discuss pros and cons, establishing practice and firming-up some opinions. Special thanks to Edward for bringing mockito to my attention.

The diagrams used in this article were produced with the excellent Excalidraw.

fin!