Amusing Ourselves to Death

Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

Summary

As of today’s date, Amusing Ourselves to Death (AOtD) scores an average of 4.15 / 5.00 over 29.5k ratings on goodreads.

AOtD is a challenging read for a short book. It is heaped in cultural criticism and a pessimistic assessment of technological development. I would not recommend readily internalising the content without thoughtful evaluation. However, much of the critique is well-reasoned and although written in the 1980s, is possibly of greater relevance today than when first penned.

An Overview of the Book

Postman’s critique is that the widespread adoption of television has subversively influenced culture, human behaviour and intellect in ways that could not be foreseen at the technology’s inception. Unaware of the broad repercussions of immersing ourselves in TV pop culture, the standards for entertainment in this medium of communication have permeated through society, from the boardroom to the classroom.

Postman warns that American culture; seemingly unaware of how trivial and distracted it has become; is at risk of losing its moral compass. The main premise of his warning is that rather than an Orwellian dystopian future where society is controlled by a despotic surveillance state, a more realistic outcome would be characterised by Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World [1]. A future where a simpleton proletariat has been rendered ineffective by the pursuit of hedonism at the cost of all else.

The book is organised into 2 parts and 11 chapters. Part 1 establishes the scale of the apparent decline in literacy, logic and debate brought about by the decline of a largely print-based culture. Part 2 argues that aspects of TV as a medium impose limitations on the length of exposition and complexity of language that have widely influenced our lives. Postman exemplifies how this simplification of our public discourse has declined, with considerations from many domains.

Part 1

The book begins with a treatment of Huxley’s warning in Brave New World. A future in which civilisation is threatened by an over-supply of information and a reduction of the peoples’ ability to identify that which has meaning. Postman suggests that Western culture had been en guarde for signs of Orwellian oppression but has not adopted a defence against the possibility that we may be oppressed by our own ignorance.

1. The Medium Is the Metaphor

Postman argues that the technological revolution brought about by mass adoption of television has unwittingly changed the fabric of our society. Using the analogy of the clock, Postman indicates that the mechanism is not merely a device used for measuring time, but that it “dissociates time from human events and thus nourishes the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences.” [2, p. 12].

This analogy does not help someone who is subject to the belief of quantifiable sequence in understanding his point. The thought of a world without clocks is an unimaginable dystopia. The positives that the clock has wrought greatly outweigh any possible drawbacks that I can conceive of. This may be the point entirely - just as the fish is likely unaware that it lives within water, the ability of the human mind to conceive of how it has been influenced by a technology that has been fully integrated through society may be similarly limited.

Postman goes on to state that the clock has removed the concept of god from the meaning of time. Unable to place a god as the cause of time, I am lost as to how to meaningfully rationalise his analogy. I surmise that Postman’s point is that as a consequence of reducing the concept of time to the machinations of gears, removes any sense of reverence or magical thought. Although some would argue that the internals of an analogue clock are a thing of beauty and the trade of the watchmaker an art. Nonetheless, the reduction of time to a gadget now worn on the wrist may have effects beyond a greater ability to manage time, possibly influencing our perception of our place in the universe. The comparison with television’s replacement of print seems to mean that there are unintended consequences owing to the adoption of a novel technology that are perhaps poorly understood. In my opinion, this is a weak analogy, lacking in consequence. I don’t believe it helps the reader orient to Postman’s main point. The negative consequences of the clock; whatever they may be; must now be broadly accepted as part of human existence.

2. Media as Epistemology

In this chapter, Postman considers the nature of truth, the acquisition of knowledge and how this has changed with the cultural trend toward visual media. The author posits the concept that all media are not equal in their ability to convey meaning and truth.

An interesting juxtaposition is explored - that in certain circumstances, the medium of spoken word is thought to be of higher merit than the written, such as in most modern courtrooms where verbal rather than written testimony is required. However, Postman is able to draw on his experience in academia to illustrate that the reverse is true in the assessment of a thesis, where a candidate had attempted to cite ephemeral evidence; a conversation or interview with an academic. In this example the result had been a witty retort from the review panel,

“…we are sure you would prefer that this commission produce a written statement that you have passed your examination (should you do so) than for us merely to tell you that you have, and leave it at that. Our written statement would represent the”truth”. Our oral agreement would be only a rumour.” [2, p. 24].

Who could argue with that? The contrast between written assessment and courtroom testimony’s truth value glazes over the context and purposes of these discourse formats. The courtroom favours verbal testimony as an unadulterated recount of the past and motive, yet quickly commits this testimony to the written word via courtroom stenographers. A raw, unfiltered account for a thesis would only serve as a draft and would require significant editing in order to test that the structure and content of the paper is robust.

Postman goes on to examine truth as a cultural prejudice for certain media. From tribal counsel’s use of parables through Aristotle’s deductive reasoning about the physical world, Postman finally rounds to the modern world’s adherence to the quantifiable.

“Many of our psychologists, sociologists, economists… will have numbers to tell them the truth or they will have nothing. Can you imagine, for example, a modern economist articulating truths about our standard of living by reciting a poem?” [2, p. 26]

I wonder if numbers can be considered a medium. It occurs to me that numbers are a language that can be expressed in a variety of media. Postman could have explored instead the danger of an over-reliance on statistics as truth. The fact that statistics can be selectively deployed to make opposing arguments is of course, not a new one.

“Lies, damned lies, and statistics.” attribution debated.

The use of numbers to oversimplify, diminish context and misdirect can also be a misuse of data visualisation. On the nature of bias in the chart,

“…it makes the viewer believe that they can see everything, all at once, from an imaginary and impossible standpoint. But it’s also a trick because what appears to be everything, and what appears to be neutral, is always … a partial perspective.” [3, Ch. 3].

All of us must be guilty of accepting a viewpoint based on the convincing support of charts or numbers, without undertaking the necessary due diligence of reproducing the analysis and seriously examining the assumptions and potential underlying biases. The complexity of society and the volume of analysis we generate make it impossible not to do so. The presumption is that those people charged with the responsibility of evidence-based policy design are carrying out the due diligence on behalf of us all.

3. Typographic America

The author uses this chapter to familiarise the reader with an abridged history of literacy from 17th century England and the United States through to modern day America. Thanks primarily to the efforts of the churches, literacy among the general populace was understood to have been significantly higher than in the modern day populace. But with a decline in the relevance of the printed word, literacy rates have steadily declined over the previous century.

17th century people were conditioned to spend long hours of leisure time focussed upon reading a single book. This mental fortitude affected their ability and predilection for other feats of mental endurance. Debating halls were common across the country and accounts of debates extending long into the evenings were said to be common. The contrast between these discussions and the modern approach to televised debates must be striking. It is here that I have little to argue with Postman’s position. It is undoubtedly true that television does nothing to prepare viewers for bouts of prolonged concentration. If a topic cannot be reduced to chunks of ten second sound bites, it generally makes for poor television.

While television is an enjoyable entertainment device, the demands of its format aim to keep the viewer perpetually stimulated and do not imbue its audience with mental fortitude. Postman’s position is that this lack of mental preparation against boredom leaves us struggling to achieve focus in many other contexts. These known limitations of television have given rise to the podcast in recent years, where a type of long format debate has returned to public fora.

4. The Typographic Mind

In this chapter the author explores how a sustained media shift away from the printed word may have influenced our assessment of culture’s interpretation of truth. The author compares the image-obsessed standards of the televised news shows to a form of infantilism. Where assessment of truth is based upon the appearance of the newscaster rather than the content of the televised message. An industry-wide ad hominem has permeated through even those shows that are intended to be sober and informative. Postman suggests that the form of truth and intelligence valued by ‘the typographic’ mind (pre-television) would have been markedly different.

An interesting point is made about an unspoken contract between television and those appearing on it. The author argues that the dominant media in our society governs the behaviours of those wishing to exploit that as a tool. Politicians, scholars and religious figures are reduced to a fickle celebrity by the demands of a television presence - curate your image, reduce your campaign to sound bites, prioritise speed over reason. In considering the first 15 presidents of the United States, Postman states,

“Public figures were known largely by their written words, for example, not by their looks or even their oratory… To think about those men was to think about what they had written, to judge them by their public positions, their arguments, their knowledge as codified in the printed word.” [2, p. 70].

Recalling any of the notable icons of the twentieth century would entail instantly recalling their image rather than the content of their words or actions. Political campaigns have been won and lost at the hands of advertisement budgets, party political broadcasts and impactful slogans. It appears that we are in the midst of fast food politics, a generation of the slogan-oriented, averse to analysis of manifesto.

5. The Peek-a-Boo World

Here, the author establishes the “information-action ratio”, a concept that considers the relevance of a communication to the person receiving it.

“…how often does it occur that information provided to you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would not otherwise have taken, or provides insight into some problem you are required to solve?” [2, p. 78]

The author goes on to qualify such exceptions to the low relevance information generally on offer by television, such as weather programming and stock movements. It is an interesting concept that I have pondered, finding exceptions here and there myself, such as programmes that help people to manage their finances, special interest programming such as gardening shows, and so on. I can only estimate how important shows such as Songs of Praise must be for those who are unable to participate in the communal observation of their religion in person. Undeniably, these shows would be exceptions that prove the rule - that the purpose of the television is primarily to entertain, even when it purports to inform.

Postman’s criticism of what has become “The News of the Day”, which he states started with the invention of the telegraph and has been further transformed by a partnership between television and newspapers into the ‘human interest’ genre, is that the information is low in information-action ratio. With the telegraph, “news from nowhere, addressed to no one in particular, began to criss-cross the nation” [2, p. 78].

This commodification of contextless information, Postman argues, was bolstered by photography. Once papers adopted the photograph, “For countless Americans, seeing not reading, became the basis for believing” [2, p. 86]. A prescient point as we enter the age of the deep fake.

The author warns that our culture is bombarded with low-relevance information and a limited capacity for sorting it based on relevance. I have found the combination of a negative news loop and continual outrage on social media to have caused a shift in my personal behaviour away from those media. Yet I also note that at the time of writing this blog, the United Kingdom has experienced its largest sustained demonstration in history. Outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas has caused people across the country to consider their own position on the matter, arousing strong emotions that have led to these mass demonstrations. Similarly during the Covid-19 lockdowns, the greater part of the nation coalesced around the television to gain their news from the Covid press briefings. While the vast majority of television’s content may be almost irrelevant to those subject to it, its ability to influence on a mass scale may be magnified during crises.

I will complete my review of Part 1 on the author’s warning that has troubled me the most. That televised media has become the dominant culture in a way that we can no longer separate the two.

“Twenty years ago, the question, does television shape culture or merely reflect it? held considerable interest for many scholars and social critics. The question has largely disappeared as television has gradually become our culture.” [2, p. 91].

As fish may be largely unaware of the water around them, we are immersed in TV culture and are generally oblivious to how this has mediated our thoughts. One could argue that the relevance of television is in decline and that newer forms of media are to dominate the future. I would argue that the addictive properties of the mobile phone tend to be those that ape features of television, albeit a television that can follow you out of your living room, accompany you on your dog walk and keep you enthralled on your drive to work. It seems that the human predilection for entertainment can subjugate notions of personal safety and consideration for others.

Part 2

6. The Age of Show Business

This chapter best represents the core of Postman’s criticism. He elaborates on how entertainment has become ‘baked-in’ to television’s format, even in the more sober programming. As the author puts it, “…entertainment is the supra-ideology of all discourse on television” [2, p. 102]. Postman argues that this exaltation of entertainment has gone on to influence the wider culture.

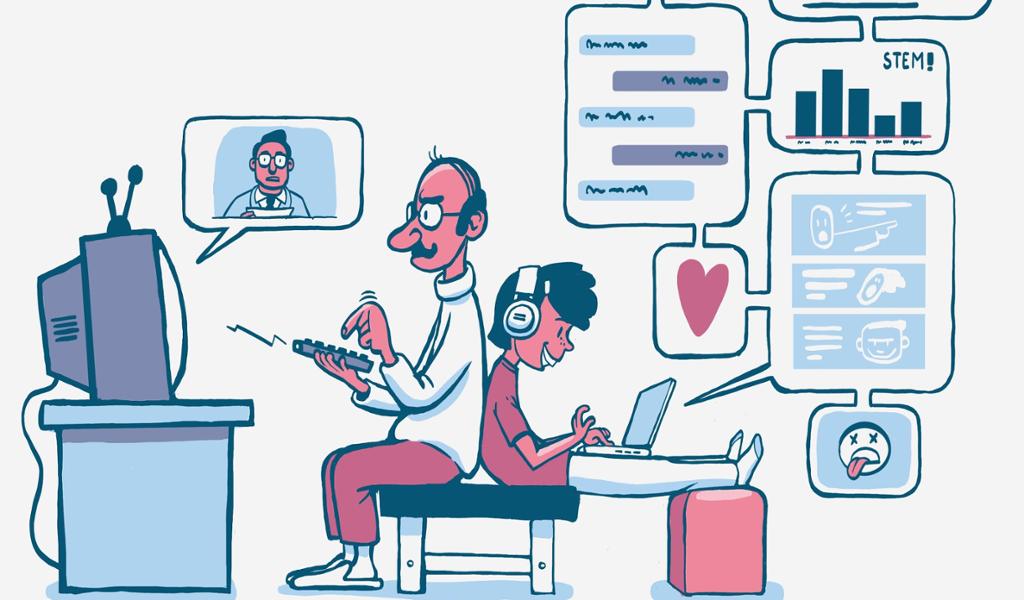

“Television is our culture’s principal mode of knowing about itself… how television stages the world becomes the model for how the world is properly to be staged…

In courtrooms, classrooms, operating rooms, boardrooms, churches and even airplanes, Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas; they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.” [2, p. 108]

If I needed to reduce the book down to one quote, it would be the above. The values enshrined by television have been broadly adopted, influencing our societal norms. Postman rightly points to limitations in television’s format that limit reasoned conversation. In its pursuit of the stimulating, television generally does not permit hesitation. Uncertainty is not tolerated on modern TV. The act of thinking does not make for good viewing. Over time, our tolerance for thinking-time in real-life situations such as the boardroom or the job interview has been further eroded by standards propagated by TV. The iconic Dragon’s Den sixty second business pitch, replete with hype and corporate speak becoming the subconscious expectation for discourse in all situations.

In recent years, the division between television and the rest of the world has reduced further still, with the ‘reality TV’ genre aiming to commodify what may be represented as everyday life. Now there are TV shows where we can watch others watching TV shows. Instagram is the social media platform where people present an idealised impression of their lives on a dedicated catwalk, while on YouTube, people and families commodify their own lives, merging their leisure time with commercial opportunities in order to monetise every waking second. It is clear that television (and its close cousins) have become inextricably linked with human experience. It is likely that rather than causing the end of television culture, the internet has served television in such diverse formats that it is nearly inescapable.

7. “Now… This”

“For on television, nearly every half hour is a discrete event, separated in content, context and emotional texture from what precedes and follows it.” [2, p. 116]

Postman applies this in what he refers to in its most embarrassing form to the news of the day shows. Updates may be broadly grouped as ‘politics’ or ‘sport’ but are scheduled to stimulate attention and emotion, in short - to entertain. Accompanied by attractive presenters, stirring music and interspersed with engaging commercials, Postman rightly points out that the viewer understands that even the most horrific article on the human impact of war should not upset the rest of their day. Quickly, the viewer’s palate will be cleansed in preparation for the next article in what has become a form of cultural voyeurism.

Postman’s point about the fragmented context of a TV schedule may be applied at a finer scale in related visual formats. Many studies have investigated change in cinema and viewer attentiveness. Cornell University [4] have investigated decline in shot duration in a broad range of movies, finding a stable trend in decreasing shot duration. The interpretation of this finding is that cinema adapts to a society with less tolerance for boredom by ensuring that the executive function of cinema-goers is not taxed. Or in the words of Ridley Scott, on his latest movie Napoleon, he constantly watches for the “bum-ache factor” [5] in his movie-goers, which I find quite fascinating - Scott’s 40 year-old science fiction masterpiece Alien is well-known to revel in longer shot durations.

This trend in shot length can be anecdotally observed in television also, especially in children’s programming. Some shows that my children adore, I struggled to ‘keep up with’ - almost anything produced by Nickelodeon. The comparison to some of the older endearing shows of yesteryear such as ‘Watch With Mother’, ‘Thomas The Tank’ and ‘The Clangers’ is stark. As culture has adopted the norms of increased segmentation, a feedback loop whereby viewers no longer wish to endure longer format media may have driven a trend toward a reduced shot duration, greater emphasis on motion and greater stimulation brought about by frequent context switching.

The author’s warning to society is that the danger of a slew of information bereft of context, relevance and meaning has left people indifferent. How can a person internalise this glut of information without being seriously affected by the scenes of crime, war and human suffering? The answer would be in a societal intellectual compartmentalisation - cognitive dissonance at scale.

“…it is far more likely that the Western democracies will dance and dream themselves into oblivion than march into it, single file and manacled… it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcotized by technological diversions.” [2, pp. 128–129]

8. Shuffle Off to Bethlehem

In this chapter, Postman explores how television has given a new platform to religion and how the norms of the television medium have influenced the content provided by religious programming. When AOtD was written in the 1980s, Postman observed that the most viewed religious content at the time had become focussed on dealing with the extremes of the human condition. Commercials showing people wracked with guilt or in desperate conditions and turning to the church for solace. Postman’s observation that extreme emotions translate to higher ratings was astute, predicting the trend for American TV evangelicals, of which the most viral have now become immortalised in memes rather than by the rapture that they tend to call for.

Which brings me to Postman’s next concern about religious show business - the unavoidable celebrity that the clerics attract. Coupled with the monetisation of modern religious viewing, a malaise of spiritual bankruptcy has been accepted in this most visible element of the modern church. Celebrity pastors become extremely wealthy while serving explosive rhetoric, using advertisement campaigns designed to prey upon misery, insecurity and vulnerability. Undoubtedly, at its worst, modern religious programming in the United States has become a caricature, a ridiculous spectacle of extremes. I note that the sort of viewing that I am selectively referring to here may not reflect all shows of this nature. In stark contrast, the BBC’s Songs of Praise could not be characterised as extreme in any way - largely due to the BBC’s public broadcasting purpose, it is not subject to the format pressures that monetisation (or arguably ratings) introduce.

Much of today’s religious viral content has great potential to misrepresent the defining features of its subject’s faith. To those passing viewers of no particular denomination, these shows often present a glimpse into a cast in the act of uncouth showmanship, rather than a community in the act of worship.

9. Reach Out and Elect Someone

A consistent thread in AotD is the change in political discourse between 1780s and 1980s America. Back in chapter 4, The Typographic Mind, Postman introduces the Lincoln-Douglas debates [6] in order to make two key points, the first being that the duration (7 hours in one sitting) and complexity of the discourse allowed a more nuanced evaluation of the positions of the candidates. The second point made was about the proposed capacity of the audience to sustain their comprehension of the complex subject matter for such an extended duration.

In chapter 9, Postman returns to this example in order to illustrate the decay in the public’s appetite for meaningful political discourse. Some of his points land well, with a stark contrast in recent years with the rise of populism and in particular the appalling and often provocative use of language during presidential debates appealing to the more base instincts of an audience. Yet something troubles me in the contrasting examples employed by Postman in order to make his point:

- How can we say with any certainty that the attendees of the Lincoln-Douglas debates had comprehended the content?

- What evidence is there that the mental faculties of the Lincoln-Douglas debates’ audience were representative of the average American?

These two key questions cannot be answered by historical accounts alone. Without testing and surveying the audience immediately on exiting the debates, it would be incorrect to draw conclusions that could be generalised to a larger population. While it may be that societal and technological change may have reduced an average person’s attention span, I would not attempt to base my argument on anecdotal supposition.

On the subject of comparing political candidates,

“…television makes impossible the determination of who is better than whom, if we mean by”better” such things as more capable in negotiation, more imaginative in executive skill, more knowledgeable about international affairs, more understanding of the interrelations of economic systems, and so on… For on television, the politician does not so much offer the audience an image of himself, as offer himself as an image of the audience.” [2, p. 155]

I would agree that the limitations in television’s format constraints make for a poor vehicle for political awareness. We have seen how televised political debates become bouts of slogans and savagery. It means a great deal if a person is not allowed to take the necessary time to process and formulate a reasoned response. The rules of the game are then not in comprehension and logic. The most effective path to success would be in securing the audience’s appeal while simultaneously eroding public confidence in the competition.

And on the point of how politics has; like many aspects of society; become obsessed with matters of image - where should we point the blame for this shallow obsession? The fact that Neil Kinnock falling over on Brighton Beach, Ed Miliband’s infamous bacon butty gurn or the media’s flare for capturing Theresa May’s most unflattering expressions likely sold more newspapers than any analysis of their respective parties’ manifestos ever did. In voting for a person instead of a party, are we not putting all of our political eggs in one basket?

10. Teaching as an Amusing Activity

Of all the different domains of society that Postman explores through his lens of discounted discourse, it was the topic of education that resonated the most with me. I should divulge that I have previously spent nearly ten years teaching high school science within the British education system.

My initial impression is that Postman is no fan of Sesame Street. As a child of the ‘80s, this is not a strong start. While not wholly critical of the Muppets-inspired preschool ’edutainment’ show in its potency as an entertaining pastime for preschoolers, Postman finds the precedent it sets for presenting television as a medium for education disagreeable.

In this chapter, the author sets out what I consider to be the most concerning element of his argument against television’s command of our culture - its ability to displace education with entertainment. This resonates with my experience in education during a period of technological advancement that must have supplanted television’s ability to interfere with intellectual advancement - the multimedia mobile phone. Postman’s technological scepticism in the 1980s may have been interpreted as antiquated at the time but to my mind this chapter is imbued with a prophetic quality.

“…television has by its power to control the time, attention and cognitive habits of our youth gained the power to control their education. This is why I think it is accurate to call television a curriculum… whose purpose is to influence, teach, train or cultivate the mind and character of youth. Television, of course, does exactly that, and does it relentlessly. In so doing, it competes successfully with the school curriculum… it damn near obliterates it” [2, p. 169].

The crucial difference between the mobile phone and the traditional television that Postman opined in the ’80s is that the phone has now become a mobile television, among many other things. The need for traditional education to compete with this alternative curriculum has introduced a great deal of friction in the modern classroom, as if there were not enough already. But for a proportion of the population, the persistent availability of entertainment over education has devastating consequences. I know this because I have seen it. For many young people, education is rarely an enjoyable undertaking and preparing themselves requires discipline and endurance. Adding a constant opportunity for distraction to this situation will render a smaller proportion of our youth unable to learn anything other than the most shallow of content. One may argue that this has always been the case, which I would not refute. My position is that the proportion of people who are unable to access the National Curriculum has grown as a result of improper technological interference.

Postman’s next point about television’s societal influence is yet more troubling. As he sets out in previous chapters, television not only presents certain standards for our intercourse, it establishes those norms for our use in society. In this context, television not only displaces education, it remodels it. On the topic of ‘dumbing down’ in educational curricula,

“Mainly, they will have learned that learning is a form of entertainment or, more precisely, that anything worth learning can take the form of entertainment, and ought to. And they will not rebel if their English teacher asks them to learn the eight parts of speech through the medium of rock music. Or if their social studies teacher sings to them the facts about the War of 1812. Or if their physics comes to them on cookies and T-shirts. Indeed, they will expect it and thus will be well-prepared to receive their politics, their religion, their news and their commerce in the same delightful way” [2, p. 179].

Curriculum-reform has faced a crisis in recent years - what should we teach children who now have the world’s information in their pocket? Education’s response to this development in the early part of the 20th century has been to strip the curriculum of content, to focus on the development of skills over knowledge. This has been coupled with prioritisation of skills in assessment frameworks. Our newfound ability to outsource accurate recall to devices has resulted in doctors that Google your symptoms, mechanics that Google engine components and data scientists that Google model parameters - I am compelled to disclose this last example, having successfully transitioned away from teaching to analysis in more recent years.

How problematic is all this change? Human recollection was never our species’ strong suit - just ask a legal professional about the fallibility of human memory. Better to outsource that to the machine, right? It is certainly convenient, and as someone who considers themselves a bit of a professional Googler, it’s undeniable that it is at times a tool for good. But is it a good idea to hand over responsibility for knowledge retrieval to the machine, or more accurately big corporations? What do we lose when we do this? What are the unseen biases and agendas in the content that is shown or censored? How are these intrinsic patterns affecting outcomes for people?

The shift from recall to a skills-based educational framework has assumed that the value of a human being is in synthesis - the ability to evaluate sources of information and to put it to work, composing novel content. As Large Language Models begin to reveal their potential in executing these higher-order intellectual functions, where do we go next? Technology’s advancement has the potential to disrupt our estimation of human value and priority. Will lack of practice in the creative endeavour reduce our species to manipulators of tools produced by the machine, or increase our capacity for creation - freeing us from time consuming, lower operations? I don’t know, but I can say that we will be discovering the answer to these questions in retrospect - realising the consequences; both desirable and otherwise; as we proceed through uncertainty.

11. The Huxleyan Warning

In the final chapter, Postman reflects upon his argument against technology, examining the readiness of American people to adopt novel technology in spite of the potential disadvantages they may incur.

“…a population that devoutly believes in the inevitability of progress… all Americans are Marxists, for we believe nothing if not that history is moving us toward some preordained paradise and that technology is the force behind that movement” [2, p. 183].

The reference to Marxism does not capture a meaningful assessment underlying the ideology. After all, Marx called for the people to intervene in the direction of their future based upon his assessment of the flaws in prevalent capitalist societies. This would not presume progress as the default position, although Marx did suggest that a system of rules limiting personal gain at the expense of others could result in a form of utopia if properly administered. I presume Postman’s comment to be a provocation of the intended audience, potentially born out of frustration at a society willing to roll the dice on progress through technology.

“Americans will not shut down any part of their technological apparatus, and to suggest that they do so is to make no suggestion at all… Many civilized nations limit by law the amount of hours television may operate and thereby mitigate the role television plays in public life. But I believe that this is not a possibility in America” [2, p. 184].

Postman makes an interesting point about directionality in technological innovation. When a novel product has non-trivial, immediate and tangible benefits you may expect it to be readily adopted. Once the economies of scale have been applied to said product and the reduction in financial cost has removed the significant barrier to accessing those benefits, I agree that our ability to reverse such widespread adoption is limited. Demand and profiteering form an economic valve that maintains the product evolution and consequent sales. The fact that the consequences of all this activity may be measured over a lifetime while the benefits may be observed within an instant is a dichotomy that the human mind appears poorly equipped to deal with. Technology may be our modern-day pandora’s box.

Finally, Postman turns his attention to the computer, where he was both right and wrong,

“Although I believe the computer to be a vastly overrated technology, I mention it here because, clearly, Americans have accorded it their customary mindless inattention; which means they will use it as they are told, without a whimper” [2, p. 187].

Here, Postman proves that a person’s biases limit their understanding of potential. In the ’80s the position of computers in our society may have been debatable, although not to the likes of Bill Gates. It’s obvious from today’s perspective that the utility of the computer has been proven. People form interests around ideas and things that align with their values, developing foresight into potential applications as they encounter problems throughout their everyday life. Postman was wrong in his assessment of the utility of the computer, but in his subsequent statement,

“…years from now, …it will be noticed that the massive collection and speed-of-light retrieval of data have been of great value to large-scale organizations but have solved very little of importance to most people and have created at least as many problems for them as they may have solved” [2, p. 187].

It is fascinating to observe this foresight from forty years ago. In the age of the multinational technology corporation, fortunes have been built upon meeting human needs. The consequent power this has produced has recently been accused of interfering; or being exploited to interfere; with democratic elections around the world. This has evolved into a power struggle for public influence between big corporations and authorities of various territories. Some twenty years after social media’s inception, governments have begun a campaign of control over social media platforms, opting to censor and police where they deem it necessary. Whether this represents infringement or protection of our rights is hotly contested. Could it be that Postman was again, partially right and wrong about the relative threats of Orwellian and Huxleyan dystopia? What if they are not mutually exclusive and what if technology enables the worst of both worlds?

Analysis and Evaluation

It would be tempting to dismiss Postman’s criticisms of television culture as an antiquated resistance to progress - this would be an ignorant treatment of his argument. Technological advancement has demonstrated its ability to transform our culture. As a species we are locked into a continual compromise of how to implement immediate benefits while avoiding the longer-term costs. When a technology’s consequences are transformational; as was the case with the printing press, the lightbulb, the nuclear bomb and the multimedia device; might it be best to proceed with caution, allowing time for a more meaningful cost-benefit analysis?

In the Imperative of Responsibility [7], Hans Jonas considers an alternative ethical framework, designed to hold those responsible of profiting from technological enterprise responsible for any remote and unforeseen consequences of its implementation. This principle is known as the Precautionary Principle and has garnered equal support and derision in academic literature. Authorities around the world have enacted the Precautionary Principle, establishing policy, regulation and; where identification of the causes of environmental degradation can be evidenced; to pursue justice.

Critics of the Precautionary Principle would argue that it significantly raises the bar to human progress and that this presents an ethical quandary. Could you imagine an alternative reality where legislation prevented mass adoption of the light bulb pending a full review of the environmental and societal consequences? How would our world have been limited by the lack of access to this invention? And then again, how would our world have changed if we had paused for more information prior to rolling out thalidomide to expecting mothers?

To undertake an assessment of the full impact of Edison’s filament lamp on society would have been impossible at that time. It would have required an evaluation of innovations that had yet to exist and processes that were yet to be understood. This would include a multitude of missing jigsaw pieces, such as a national-scale power grid (that would only come to be some half a century after Edison perfected his initial design), an awareness of the greenhouse effect and how electricity generated by fossil fuels contribute to this (legitimacy still argued in some circles), the study of human circadian rhythm and how this would be disrupted by the invention, an evaluation of the impact of light pollution and so on. At the same time, the case for the technology would need to be evidenced in greater measure. Evidencing the benefits to productivity, safety, leisure and wellbeing that mass adoption of the light bulb would induce would have been a monumental undertaking. This is to say nothing of the consequential innovations that either required or were inspired by the filament lamp, or that in time we would improve it, producing brighter, more efficient devices that would mitigate much of that initial risk yet cause new environmental consequences related to the use of plastics and production and safe disposal of semiconductors.

The effort described above may have delayed the mass rollout of the lightbulb by half a century or more. Time therein where the world literally sits in the dark, awaiting the bureaucracy to arrive at a decision. Preparing the world for a transformational technology may be considered an intractable problem. The Collingridge dilemma states that until a technology has been embedded in a society, there is not enough information to provide an informed assessment of its risk, and then as a consequence of the widespread adoption, an inability to effectively regulate that technology. That doesn’t mean we get to wash our hands of the responsibility of doing this - not at all. A full and unbiased evaluation of the consequences of innovation that is proportionate to the current evidence of risk would be a vast improvement over a system accelerated by profit and disregard for all else. Political lobbying, the reproducibility crisis in many fields of research and our chronic inability to identify and prosecute fraudulent behaviour have resulted in an economy where the cost of hindering technological progress outweighs the consequences to its proliferation. To put it bluntly, we have a prenatal societal capacity to defer gratification.

With the scales tipped in favour of progress above all else, the ramifications for a society at the inception of generative artificial intelligence are clear. As artificial general intelligence now appears more feasible than ever, many people of influence are involved in a rich ethical debate.

In AI, the ratio of attention on hypothetical, future, forms of harm to actual, current, realized forms of harm seems out of whack.

— Andrew NgDecember 18, 2023

Many of the hypothetical forms of harm, like AI "taking over", are based on highly questionable hypotheses about what technology that does not…

Earlier this week, POTUS Biden issued an executive order on artificial intelligence – a breakthrough technology that has the power to change the world in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

— Barack ObamaNovember 3, 2023

I wanted to share some of the books, articles, and podcasts that have helped shape…

Whether or not the future risks of generative AI will be well-managed will be based upon the conversations that we have today. At this juncture in our history, the role of the sceptic may be more vital than ever. It is not enough to sway opinion by preaching calamity or pigeonholing criticism as antiquated techno-scepticism. Finding effective modes of discourse to help promulgate AI awareness is the route to ethically achieve the integration of this latest transformative technology. The only means to navigate this milestone must be to deepen our understanding of the technology and each other. To this end I would encourage the use of open source AI tools, to discuss the implications, benefits, limitations, biases and drawbacks. Educate yourself on the direction of the research and to attempt to stay abreast of the news in the sector, while avoiding tabloid sensationalism.